As Reviewed In ATADA News

IN SEARCH OF NAMPEYO:

The Early Years, 1875-1892

Steve Elmore

Review by Billy Schenck

www.atada.org

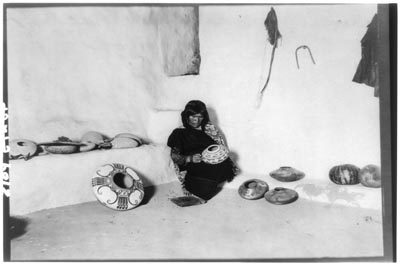

Steve Elmore’s In Search of Nampeyo, The Early Years, 1875-1892 is an eye opener. Elmore spent twenty years researching and visiting permanent collections around the country looking for and discovering the work of Nampeyo. This book of Elmore’s revelationary work could have been his PhD thesis. He probably would have been thrown out of any doctoral program if he told his advisor in advance that he was going to write his book in the first person. That isn’t done in the academic world, however what an exciting page turner this project turned out to be as a result. The credibility of his research is there in every nook and cranny as well as every page.

Elmore has thoroughly done his research and as a result, discovered incredible facts that fly in the face of conventional wisdom concerning previously held beliefs about Nampeyo and her work. His discoveries present direct challenges to concepts put forward by Wade and LeBlanc. Elmore addresses the two positions in art history in regard to unsigned works, which is really the crux of this entire study.

In 1890 the census taker assumed that every head of a Hopi household – a female was a potter. All the males were listed as farmers and weavers. According to this record keeper, that translated to 366 potters at Hopi. Pretty interesting stuff considering that number included all the adult women on all three mesas when it was also a well known fact that the potters were primarily located on first mesa. The women of second and third mesa produced baskets. Even to this day that dynamic remains true.

Another census taken in 1900 lists three women as commercial potters, Nampeyo, an aged Navajo woman married to a Hopi man and a 49 year old Hopi woman. Elmore doesn’t say it, but it sure sounds like the 1890 census taker was maybe doing a little racial profiling when listing the occupation of the other 363 “women as potters.”

This is just one example of how Elmore addresses throughout this book the myth of the existence of many Hopi potters, rendering it impossible to discern Nampeyo’s work from the rest of these ghost potters.

Elmore has documented here, every known Anglo photographer and visitor that came to Hopi from 1875 to 1892. They all name only Nampeyo as the single master potter of the time.

It couldn’t have been better conceived if this journey had been written as a movie script, to have Elmore come at last to the Peabody Museum to see the Keams Collection. By now he has visited all the other public collections that contain documented work by Nampeyo. He has an intimate knowledge of Nampeyo’s work. What he discovers at Harvard is the mother lode of Nampeyo’s early work. Her Walpi influenced Polacca work and early examples that would inform her later classic period of work, that of the Sikyatki revival.

This is one grand exciting vision quest that Elmore takes us on, not unlike the search Henry Morton Stanley made for Dr. Livingstone in the heart of Africa in 1871.

The Early Years, 1875-1892

Steve Elmore

Review by Billy Schenck

www.atada.org

Steve Elmore’s In Search of Nampeyo, The Early Years, 1875-1892 is an eye opener. Elmore spent twenty years researching and visiting permanent collections around the country looking for and discovering the work of Nampeyo. This book of Elmore’s revelationary work could have been his PhD thesis. He probably would have been thrown out of any doctoral program if he told his advisor in advance that he was going to write his book in the first person. That isn’t done in the academic world, however what an exciting page turner this project turned out to be as a result. The credibility of his research is there in every nook and cranny as well as every page.

Elmore has thoroughly done his research and as a result, discovered incredible facts that fly in the face of conventional wisdom concerning previously held beliefs about Nampeyo and her work. His discoveries present direct challenges to concepts put forward by Wade and LeBlanc. Elmore addresses the two positions in art history in regard to unsigned works, which is really the crux of this entire study.

In 1890 the census taker assumed that every head of a Hopi household – a female was a potter. All the males were listed as farmers and weavers. According to this record keeper, that translated to 366 potters at Hopi. Pretty interesting stuff considering that number included all the adult women on all three mesas when it was also a well known fact that the potters were primarily located on first mesa. The women of second and third mesa produced baskets. Even to this day that dynamic remains true.

Another census taken in 1900 lists three women as commercial potters, Nampeyo, an aged Navajo woman married to a Hopi man and a 49 year old Hopi woman. Elmore doesn’t say it, but it sure sounds like the 1890 census taker was maybe doing a little racial profiling when listing the occupation of the other 363 “women as potters.”

This is just one example of how Elmore addresses throughout this book the myth of the existence of many Hopi potters, rendering it impossible to discern Nampeyo’s work from the rest of these ghost potters.

Elmore has documented here, every known Anglo photographer and visitor that came to Hopi from 1875 to 1892. They all name only Nampeyo as the single master potter of the time.

It couldn’t have been better conceived if this journey had been written as a movie script, to have Elmore come at last to the Peabody Museum to see the Keams Collection. By now he has visited all the other public collections that contain documented work by Nampeyo. He has an intimate knowledge of Nampeyo’s work. What he discovers at Harvard is the mother lode of Nampeyo’s early work. Her Walpi influenced Polacca work and early examples that would inform her later classic period of work, that of the Sikyatki revival.

This is one grand exciting vision quest that Elmore takes us on, not unlike the search Henry Morton Stanley made for Dr. Livingstone in the heart of Africa in 1871.

Email the Gallery about this item